There are three ways we interact with Blue Crab. We issue commands from the terminal, inside the BASH shell; we transfer files to and from the machine; and, we edit text files. Unless you prepare an entire calculation on your local machine and then upload ot to Blue Crab, you will almost certainly need to edit a text file.

This section covers the bare minimum required to use

vito edit a text file. If you have another preferred editor, or are otherwise comfortable editing files in Linux, you are free to skip to the next section.

Making a blank file

Before we edit a file, we will first create a blank file using the touch command.

$ touch my_script

$ ls -l

The file listing should show that your file has been created. Let’s see what’s inside. Use the more and cat commands to show the contents

$ more my_script

$ cat my_script

Both of these report that the file is empty. The more command is useful for scrolling through long text files while using the spacebar to advance your view. The cat command is short for “concatenate” and takes multiple arguments, printing the contents of each file argument to the screen. This can be useful for joining many text files into one larger text file.

Escaping a program

Whenever you see the --More-- text at the bottom of the screen you can use the spacebar to advance or q to exit. You can also use q to exit manual pages and results of the less command, which is similar to more but offers vi functionality we will describe below.

If you’re really stuck inside a program, you can use ctrl+c to interrupt it. Use this sparingly, as some programs will completely exit when you do this.

Editing the file

Open the file using vi or vim, which is short for “visual”.

$ vi my_script

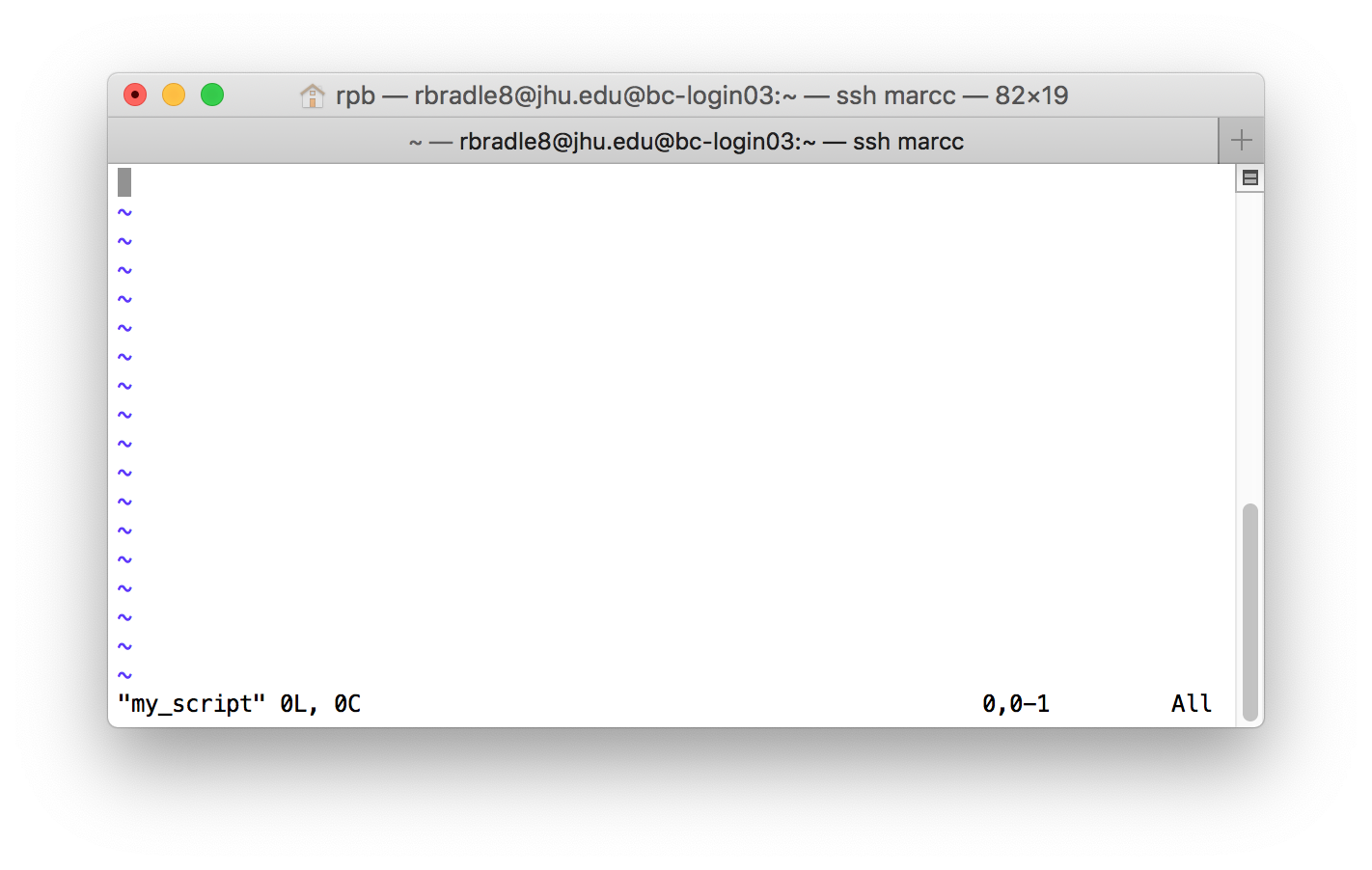

Vim is a two-mode editor which means that you must carefully pay attention to which mode you are using. It has innumerable advantages over modeless editors which are said to make your fingers gnarled from pressing the control key so much.The visual editor looks like this:

Sometimes there is useful information in the bottom row. The bottom right shows the line and character number we have selected. The tilde characters (~) indicate the absence of text.

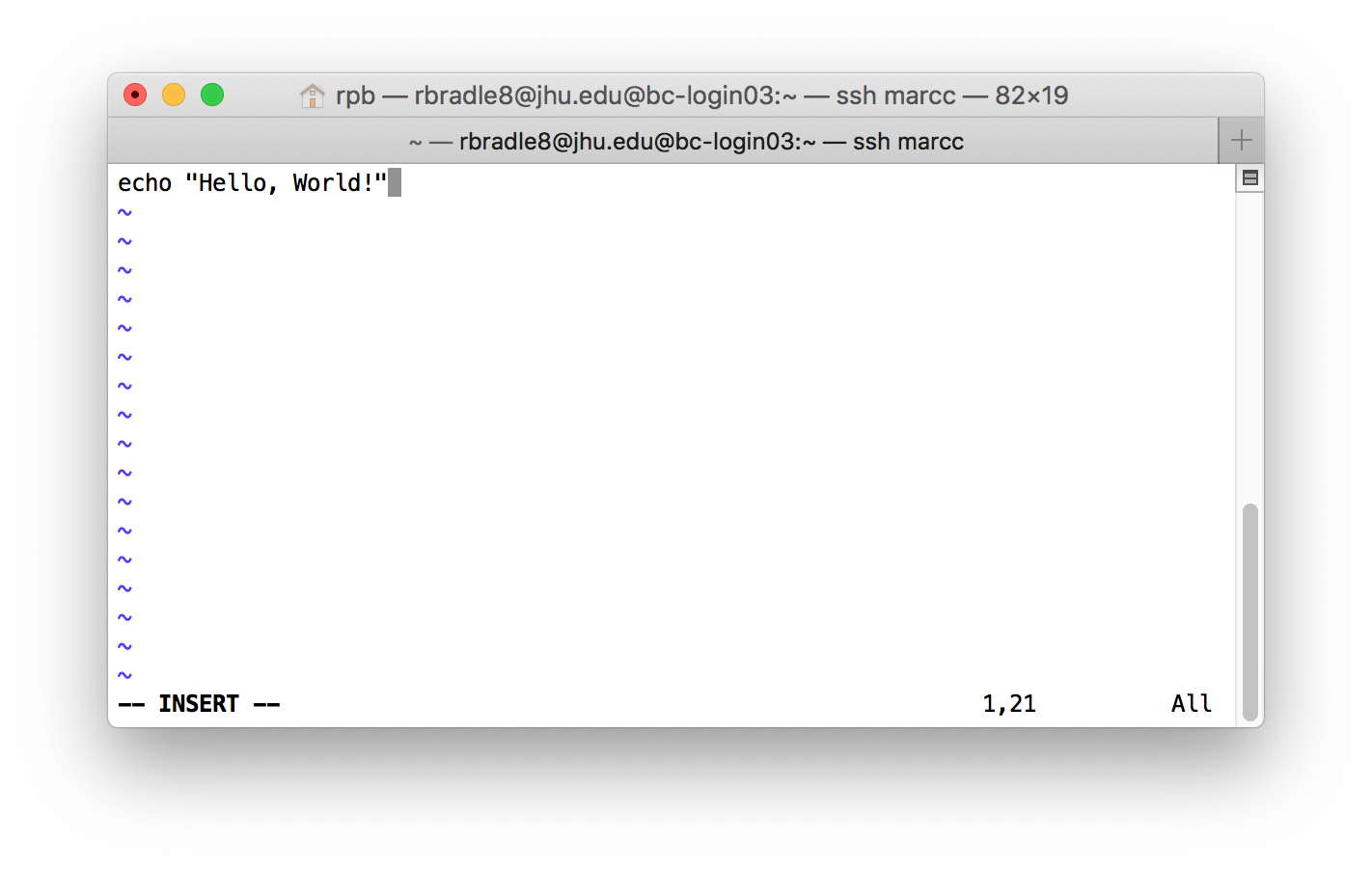

We are currently in the command mode, which is designed for issuing commands and selecting text. Use the i key to switch to the insert mode and the escape key to return to the command mode. It is absolutely critical that you understand the difference between these modes. You can always tell when you are in the insert mode because the word -- Insert -- appears in the bottom of the screen.

In the insert mode, you can enter text. Let’s write the echo command shown below.

A batch script is a text file that holds a series of commands (a “batch”) that you might enter directly into the terminal or shell (N.b. these words mean the same thing). In the example above we have written a command that echoes some text to the terminal. The echo command is actually a program which takes many arguments, all text, and simply repeats them.

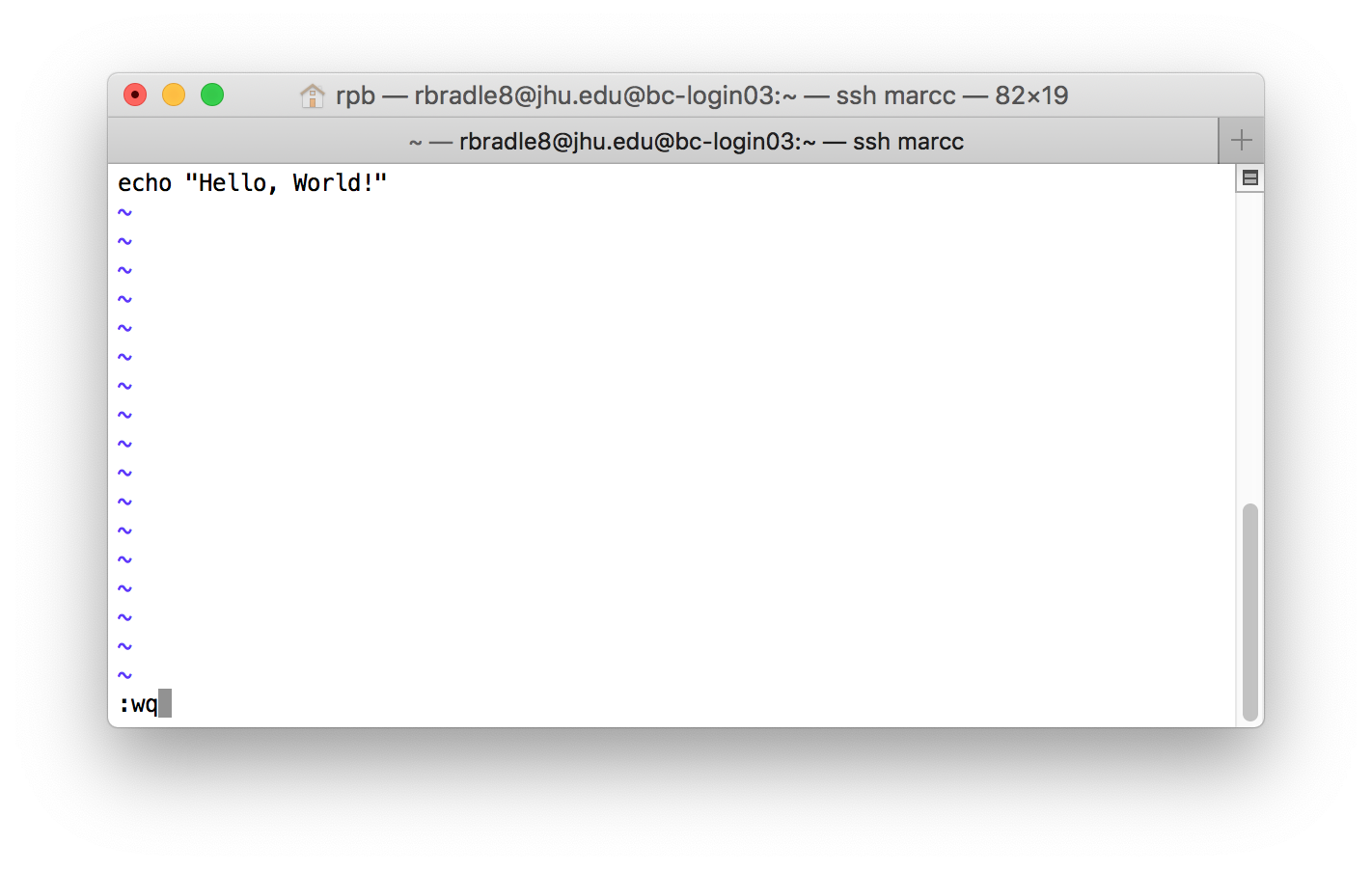

Now that we have entered some text, we will use the command mode to save the file and exit. First, use escape to enter the command mode. Open the command prompt with a colon character : which will appear in the lower left. While many commands can be executed directly, the command prompt accepts more complicated and useful commands. Type wq, which means “write and quit” in the command prompt and hit enter. The program will save the file and exit.

Now that you are back on the command line you can use more or cat to see the file.

Executing a script

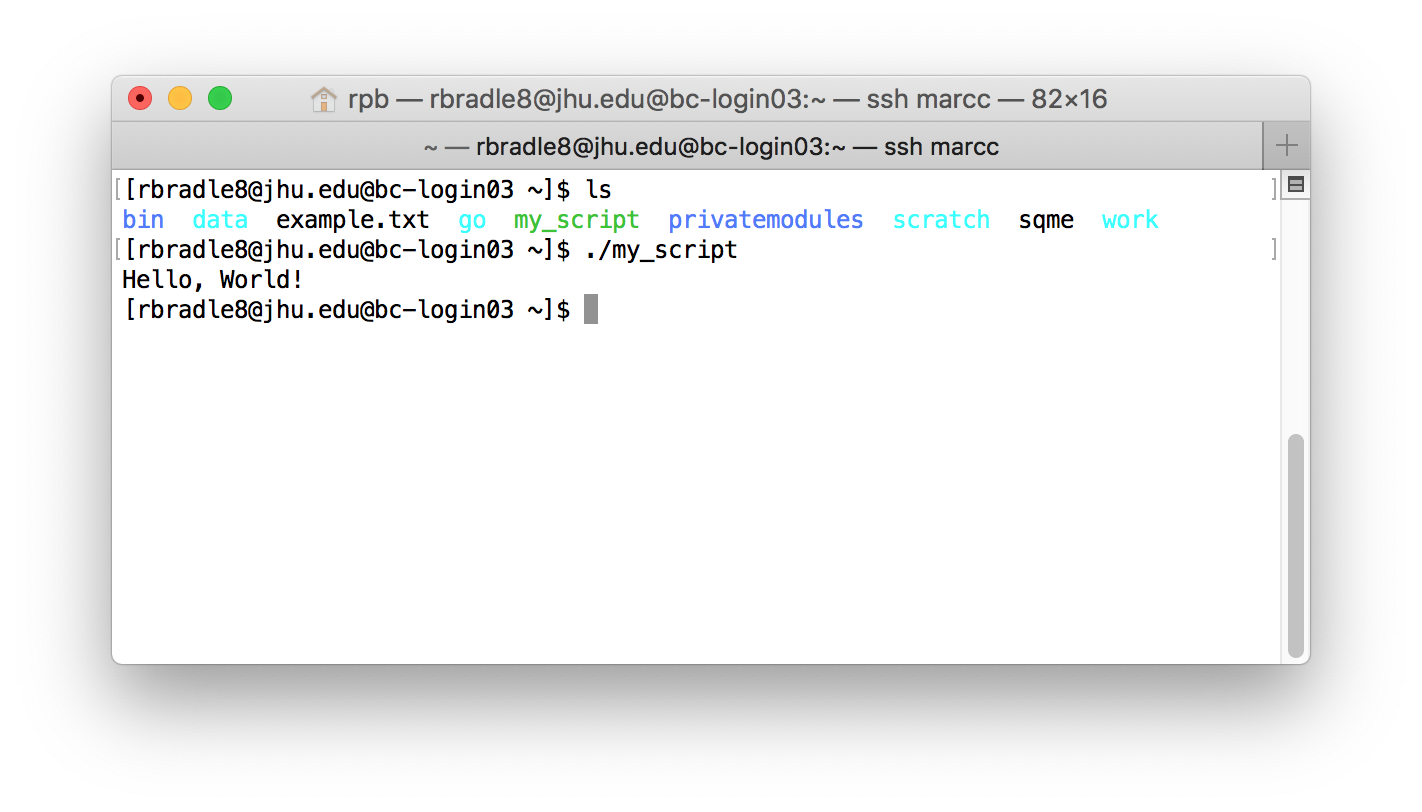

Our BASH script called my_script is one of the shortest scripts you could write. Execute it with the bash program. You are currently inside a BASH shell already (which we call the “login shell”), but you can use the bash program to execute a script inside of a sub-shell. You could just as easily run the echo command yourself.

$ bash my_script

Hello, World!

$ echo "Hi, there!"

Hi, there!

Hashbang: or, what is a program?

There are two kinds of files on any computer: binary or text. Files which are encoded in a binary format are not readable by human beings and produce a garbled mess when you try to view them with cat. Text files are readable by humans but meaningless to a machine. To execute a text file, we require either an interpreter which carries out the instructions in the text directly, or a compiler, which translates the text into binary which can be then executed by the machine.

For the first portion of the short course, we will deal exclusively with interpreted languages to avoid learning how to compile code. You have already used one of the most popular interpreted langauges, BASH, but are probably also familiar with Python, Perl, R, and BASIC. We say that compiled languages like Fortran, C, and C++ are low level languages not to demean them, but to indicate that they are closer to machine language. These days, however, the distinction becomes blurry as many interpreted languages can compile to fast machine code.

In the exercise above, we invoked the BASH interpreter using the bash command to interpret and thereby execute our short program. Our script, my_script is a regular text file. We can turn it into an executable program by adding the hashbang, which is a piece of text at the beginning of the script that tells the computer how to execute the program.

Open my_script with vi using vi my_script. Enter the insert mode with i. With the cursor on the first character, use the enter key to add a new line containing our hashbang: #!/bin/bash. When you are done, the script looks like this:

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello, World!"

Save the file using the method we learned above. At this point the file is still a text file. The hashbang is useful only for documentation purposes, because it signals to other readers that this is indeed a BASH script. Using the correct hashbang also produces helpful colors called syntax highlighting in vim which will be helpful for catching errors later on.

To turn the text file into an executable, run the following command. After you run the command, the file name will turn green if you list this directory.

$ chmod u+x my_script

$ ls

The chmod command changes the permissions on the file. You may remember the permissions code from our first encounter with ls -l earlier. The u+x argument tells the system to add execute permissions for the user i.e. owner of the file. Once you do that, you can execute the program directly using the ./ without telling the machine to use BASH.

Using the environment

Later we will learn how to effortlessly switch interpreters by manipulating our environment. We can use the following hashbang to ask the environment which interpreter to use. For example, a Python hashbang should look like this:

#!/usr/bin/env python

This translates to “use whichever python is available” as long as we have already set execute permissions on the file. Using this hashbang ensures that our scripts can later migrate to other systems without needing to know the precise location of Python. The bash interpreter is always located at /bin/bash, however many other interpreters can be found at other locations.

More information about vi

A full introduction to vi or vim (one is the “improved” version of the other but they are nearly equivalent for our purposes) is beyond the scope of this course. For now, here is a list of my favorite tricks, which are all used in command mode.

- Entering

:500will take you to line 500. - In command mode,

omakes a new line. - To delete a line, use

dd. - To repeat any command, simply enter a number beforehand.

- To undo a command, use

u. - To redo a command, use control+R

For more vim tricks, check out this guide or search for innumerable others.